Filming with Firearms

Tips on getting the shot you want and keeping your crew safe

by Dave Brown

It’s been said that if you find a job you love, you’ll never work a day in your life. In a career now spanning 35 years of handling firearms in film, theatre and opera and collaborating with actors to protect their safety and make them look real, I don’t think I’ve actually worked a day in my life. And I’ve loved every minute of it.

Even more importantly, I’ve managed to learn a few things about safety and the use of firearms in the entertainment industry.

One of the most important lessons I ever learned, is the lesson I learned on day one.

I don’t work with guns; I work with people.

Filmmaking is a collaborative process. Every job on a film set is important. Coordinating the safety of firearms may be one of the more unique occupations in the industry, but the role is still one very small cog in a very large wheel. All of those ‘cogs’ need to work together to get the shot quickly, safely and within budget.

This is why there is often a close relationship between the cinematographer and the professional firearms safety specialist. We are all there to help get the shots they want, and get them safely. Good experts know they are there to work with great people to help get great shots that tell a story.

So why pay the cost to have an expert on set, especially these days when we can just hand out replica guns, say, “Here. Act,” and fix things in post? Why bother hiring experts when one can find amateurs willing to work and who have some kind of license in their pocket? They are just handing out props after all. They can hand them out and walk away to do other props jobs.

In 35 years, I have never taken my eyes off a firearm being used in a scene or a rehearsal, and I never will. Anyone can call themselves an armorer. Not anyone can do more than just supply guns.

Firearms safety professionals are there to make sure everyone on set can relax and do their jobs without worrying about the safety of firearms. This is why, in Manitoba where I am from, we title the person who is directly on set to protect the safety of cast and crew, make the cast look good and help make the scene look believable, as “Firearms Safety Coordinator.” Only amateurs think we are there just to hand out guns.

"Productions not willing to pay the cost for a professional will be shocked at the cost of employing an amateur."

Expertise Costs MoneyWhy spend the money? The answer lies in maximizing the potential of your cast and crew. They need to be calm while they go about their jobs, not worrying about their safety because someone constantly reminds them how dangerous firearms are, or runs around yelling something idiotic like “fire in the hole!” when guns are loaded with blanks. Safety is not about scaring people. It’s about treating firearms with respect, consistently checking every firearm on set and working with the same quiet, calm professionalism as a good camera operator.

The mark of a good firearms safety coordinator is knowing our jobs so thoroughly that we can almost always find a way to get you the desired shot. This is why an “expert” cannot be just someone with a license or certificate hanging on their wall. A firearms license doesn't make anyone an on-set expert any more than a driver’s license makes one a stunt coordinator.

Firearms experts know guns as much as cinematographers know lenses. We know safe distances and angles. We know when we need safety gear. We know how to safely get gunshots with blanks at almost any distance you desire. But good firearms experts also know the importance of not just working with guns, but the importance of getting along with people. We are not on set to instil fear. We’re there to inspire confidence. We may know when we need to say “no” but, just as important, we know how and when to say “yes.”

The need for expertise is not restricted to real firearms. There are risks even with fake firearms. We all know the costs of using amateurs or doubling up crew positions, but other less-obvious cost-cutting measures such as using all replicas and generating all the muzzle flashes in post can also hurt performances. Actors hate having to act with what are essentially toy guns in their hands. They have all seen really bad visual effects. They already know, unless you spend time preparing for CGI scenes and using experts who know what they are doing, the lack of heft and noise can make the scene seem fake, and bad techniques from lack of proper training can make them look like amateurs.

"If an actor makes a mistake, they get another take. If the weapons handler makes a mistake, you will read about it in a thousand newspapers in the morning."

Regardless of real or fake, when firearms are on set, you should be able to glance around and find an experienced firearms safety expert standing near the camera to give guidance to cast and crew.

There is a saying that amateurs practice until they get it right; professionals practice until they can’t get it wrong. Handling the firearms on a film set should be as important to the cast and crew as the packing of a parachute is to a skydiver. Skydivers don’t get their parachutes packed by the amateur who finally got it right after ten tries; they get them packed by the professional who hasn't gotten it wrong in 30 years.

Productions not willing to pay the cost for a professional will be shocked at the cost of employing an amateur.

Working with Blanks

A blank is a cartridge that has no projectile but is loaded with enough gunpowder to create a bright flash at the end of the barrel, thereby convincing the audience that the gun has been fired.

Ironically, the flash at the end of the barrel is pure Hollywood. Real firearms rarely have any muzzle flash. The gunpowder in a real cartridge is designed to burn within the length of the barrel. In order to burn in front of the muzzle and create that bright flash, blanks need far more gunpowder than the actual cartridges they are designed to simulate.

Even without a projectile, the burning flame, hot gases, and debris from burned and unburned flakes of gunpowder create a very real hazard at close distances. However, these hazards are based on physics and can therefore be predicted and controlled by someone who knows what they’re doing.

The muzzle flash from a blank is very brief. Although our eyes can usually see it clearly, that flash only lasts a fraction of a second. Gunshots from modern rifles and handguns are not likely to be captured on any more than one or two frames. Even then, there is no guarantee that you’ll capture a good flash. This is where experience is invaluable. Skilled cinematographers and camera operators know that a flash might only be captured in one out of three or four gunshots. How do we resolve this? You can sometimes optimize capture with variable shutter angles and frame rates, but when we need one nice, clean muzzle flash, the solution is often as simple as shooting another take.

You can actually tell when you’ve captured a good flash. If you are shooting on film and you see a good flash in the monitor or eyepiece, trust me - it was not captured on the film frame. Shoot another take. If you’re shooting digital, the opposite is true. If you like what you see on the monitor, it is there. Digital also gives you the advantage of playback, so you can immediately check to make sure you got a good flash.

If the muzzle flash ended up invisible, truncated or maybe just a puff of smoke, shoot another take. Every time I hear someone say, “Let’s move on. We’ll fix it in post!” I die a little bit inside. As a perfectionist, I want to fix it NOW, and it’s often as simple as reviewing the footage and shooting another take. We are not special effects; we can do quick resets.

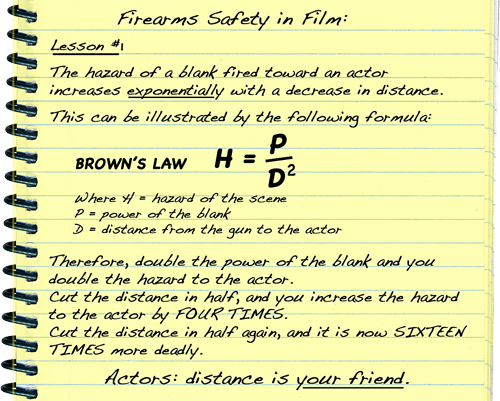

Brown's Law

Blanks expel gunpowder and hot gases out of the front of the barrel in a cone shape. This is harmless at longer ranges, but the explosion can seriously injure someone if too close. Early in my career, I wanted to find a simple way to explain these hazards and readjust the setup as required.

I tried to define how to predict how the hazard may change when distance and the power of the blank may change, so I created a simple construct to show how the hazard of a scene involving a blank is directly proportional to the power of the blank, and inversely proportional to the square of the distance away from the gunshot. As a formula, it looks like H = P/D2, where H is the hazard of the scene, P is the power of the blank, and D is the distance from the muzzle of the gun to the actor or crew standing in front of it.

During the design of a firearms safety training course for all IATSE film and theatre technicians, the Training Trust Fund kept referring to this as “Brown’s Law.”

You can’t just plug numbers into a calculator, but the formula offers a good illustration of why shooting some scenes are easier than they first appear, while other “simple” scenes can cause nightmares. The single most important factor in the safety of your cast when firing a blank is sufficient distance. Distance is your friend. We can protect your crew with safety gear; we can’t always put safety gear on actors.

We can employ blanks with varying amounts of gunpowder that gives us different power levels and adds further control over the hazards, but that is not always possible. If we substitute a half-power blank for a full-power blank, we cut the hazard to anyone standing in front of that gunshot by half. But semi-automatic and automatic firearms require a certain power to cycle the action properly, and using an underpowered blank can result in serious — and very dangerous — jams.

This is why we use distances and angles to keep actors safe, and we always plan for the most powerful blank available to us. Loaded or not, firearms and replica firearms should always be aimed slightly to the side of another person. But no matter how much we cheat the angle, we still need to allow for a ‘human factor’ because actors can make mistakes, miss their marks or approach too close.

This is why, in practical terms, the majority of gunshots in motion pictures are done as a tight shot on the actor firing the gun. There is usually no reason why we need the actor getting “shot” to be in the same frame at the same time.

But don’t forget, safety does not end with the cast. Even though the actor getting shot might be relaxing in their trailer, your camera crew will still be in front of the gunshot. Protecting the crew and the camera is every bit as important a part of the job. Brown’s Law still applies.

Safe distances vary widely depending on the load and the type of firearm, which is why we test everything in advance. But I’ll share a secret. Normally, I take the distance that people need to be away from a gunshot, and then triple it. We now avoid dangers that can result if our safe distances get gradually inched closer or when a full-power blank has to be quickly substituted for a half-power or quarter-power blank to achieve a better look. Tripling the distance also provides one extra redundancy that allows for the human factor.

Modern wraparound safety glasses and face shields do an excellent job at protecting from debris. They are made from a material called polycarbonate, which provides good impact protection. That thin shield of polycarbonate will protect against blast debris, metal shavings or the force of the explosion from even full-load blanks at contact distance. Wear your safety gear and make sure your crew does, too.

Actors don’t always wear earplugs, which in wide outdoor spaces, it’s more a matter of choice and personal comfort level. The sound of a blank may seem loud, but it does not contain the same damaging frequencies as the sound of a real bullet when it breaks the sound barrier just in front of the muzzle. But hearing damage is cumulative. In tight spaces or at close range, everyone should be wearing earplugs. Plus, the sound in front of the muzzle is significantly higher than from behind, so camera crews should also be wearing both face protection and good-quality earmuffs.

I often bring several sets of electronic muffs for the camera crew because active hearing protection can also amplify ambient sounds while cutting out the sound of a gunshot.

No one should be injured for the sake of a movie. Remind the crew that no one looks like a hero because they forego eye or ear protection. Eyes can never be replaced, and long-term hearing damage can never be undone.

Working with Great People

The best part of a career in film is the opportunity to work with so many amazingly talented actors and cinematographers. One of the highlights of my life was teaming with cinematographer James Glennon, ASC and actor Robin Williams on the 2005 film “The Big White.” During shooting, I quickly found out that beneath the humour, Robin Williams never missed a single detail.

Many of our scenes involved a revolver. Every day I would show him the empty firearm, load six dummy cartridges into the chambers so it looked fully loaded to camera, and demonstrate that it was completely safe by pointing it in a safe direction and pulling the trigger eight times.

Over the course of two months, he silently observed that I always pulled the trigger exactly eight clicks — two more than necessary for the revolver’s six chambers. Then on our final day, as I was preparing for our last scene together, Robin asked me why I always pulled the trigger eight times. I told him that I had a very personal reason for pulling the trigger eight times instead of six. “The first six are for you, the seventh one is for me, and the eighth one is for Brandon Lee.”

Robin simply said, “Thanks Dave.” This was the man who delighted and amused us non-stop while on set, and knew at this moment that he had said all that needed to be said.

In the film business, lessons are sometimes learned the hard way. I will never forget that if an actor makes a mistake, they get another take. If a weapons handler makes a mistake, you will read about it in a thousand newspapers in the morning.

****

Based in Winnipeg, Canada, Dave Brown is a professional firearms instructor and one of few civilians in Canada considered an expert in police weapons training. He has worked with military, police and government agencies on advanced shooting skills, been an Expert Witness in court, lectured at the University of Manitoba School of Law and addressed the Standing Committee on National Security at the House of Commons in Ottawa. As subject-matter-expert in the design of the Canadian Firearms Safety Course program, he helped write the book on firearms safety in Canada. Dave has written over 80 magazine articles that were published in a wide variety of police and trade magazines.

Noted for a calm approach and a relaxed teaching style, Dave has worked with actors on film, theatre and opera sets and helped write the firearms safety training module for all film and stage technicians in North America. He has been invited to speak on the topic of firearms safety in film across Canada and the U.S., appeared on CNN and the Discovery Channel and been interviewed by media from around the world. In 2018, Dave Brown was presented with a lifetime achievement award for his work behind the scenes in the Winnipeg Theatre community.